The blog of Justin Gerard: http://quickhidehere.blogspot.com/

Dragons have personalities – they aren't just lizards with wings. Justin Gerard explains how to reflect this in your art.

I've always loved dragons. And I've always loved dinosaurs, too. But dragons are not the same as dinosaurs. While I love studying the creatures of this world for clues on how to make a fantastic creature feel like it could exist in it, I think that by making dinosaurs and dragons interchangeable in our work, we're losing integral parts of what have made each one special in history, myth and fantasy.

In this workshop we're going to examine why character and personality are important in dragons, and then work through examples on how to imbue them with character.

1. Give your dragon a story.

JRR Tolkien makes a compelling case for a distinction between dragons and dinosaurs in his essay, On Fairy-stories. In it, the author recounts how when he was introduced to the subjects of zoology and palaeontology at an early age he was told by his elders that dinosaurs were, in fact, dragons.

Tolkien wanted adults to recognise the distinction between fact and fantasy, and not to dismiss one in favour of the other. He wrote: "I was eager to study nature, actually more eager than I was to read most faerie stories. But I did not want to be quibbled into science and cheated out of faeries by people who seemed to assume that by some kind of original sin I should prefer fairy-tales. But according to some kind of new religion, I ought to be induced to like science."

2. Dragons have motive.

Dragon's have a motive, says Justin, and more often than not it involves greed for gold

In Smaug, Tolkien's dragon from The Hobbit, we find a creature that provides more than just the mere threat of physical violence. He also offers a personification of greed – and a distinctly aristocratic greed at that (he refuses to share or redistribute his wealth, instead pointlessly hoarding it for centuries in his vast cave).

In John Gardner's Grendel, the dragon is even more of a philosophical threat over a physical one. The dragon reveals to Grendel philosophical principles that he wrestles with, and is ultimately overcome by. This leads him to choose to become, and even embrace, his position as the villain in the Shaper's story.

The dragon in Grendel personifies a deeply nihilistic view of the world: his final argument is about the purpose of life being that all human values are baseless and that everything we do will be made irrelevant. His best advice to Grendel therefore is to, "Seek out gold and sit on it," as nothing really matters anyway.

Gardner cleverly uses both the imagery and the archetype views of the dragon to convey how threatening and dangerous the idea is, and this belief is ultimately played out through Grendel's own final meeting with Beowulf. Like these excellent examples, give your dragon a story!

3. Use Symbolism.

Dragon symbolism offers something far more than a struggle of man versus nature. It does what fantasy does best: offers physical examples of man's internal struggles. It also reveals a wealth of other conflicts, external and internal. Not all dragons are evil. In Kenneth Grahame's The Reluctant Dragon, the writer acknowledges the classical archetype for a dragon, but flips it on its head to give the dragon a good heart.

The dragon in this story understands her design is one of evil, but chooses to rise above it. She prefers tea parties and poetry recitals to pillaging and burning. A wealth of personality can be poured into a dragon, all the while keeping its sinister features.

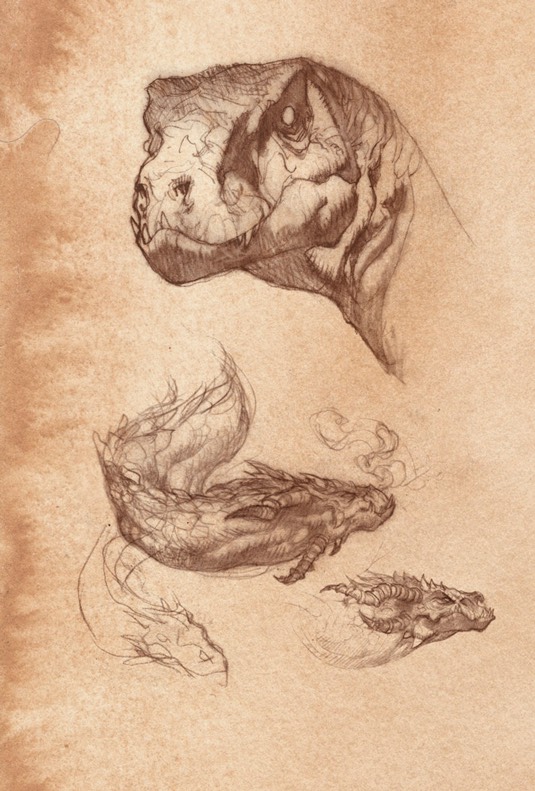

4. Draw from life.

As you draw from life or photos, make mental notes about your subject. How far are the eyes from the mouth? How large is the upper jaw compared to the lower? As you draw these details you're adding them to a mental library you'll be able to pull from in future. It also broadens your overall understanding of the construction of living things.

While dragons have a largely spiritual dimension to them, they also exist in the actual world. Therefore we should seek to make them look like they belong here.

When we're searching for something to use as physical reference for dragons there are many creatures alive today that provide us with a great wealth of material. Crocodiles offer what, is perhaps, the best and most threatening example. Of all modern-day lizards they are some of the most brutal and terrifying in appearance.

5. Use human reference too.

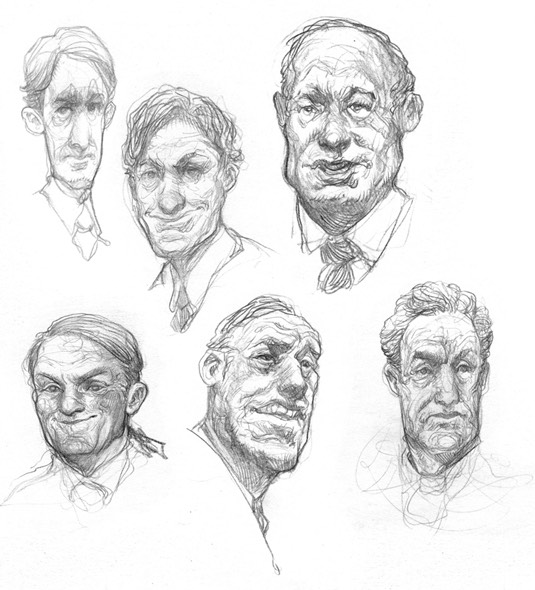

By making studies of human faces and expressions you'll soon find they creep into your art

We're searching for a visual balance between a creature that captures our sense of reptilian evil and human intelligence. For humans, I'll occasionally use pictures of myself (I can look shockingly sinister at times).

But I also keep a folder of images from the news of sinister-looking political figures – there are some wonderfully sinister politicians out there! So, a brief foray onto political websites turned these curious figures up.

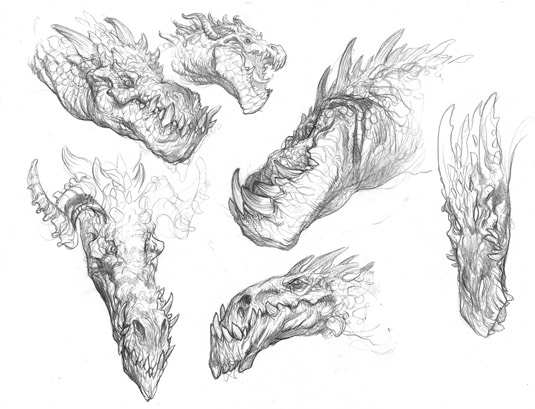

Now that we have good references for human expressions of deviousness, we can turn to our dragons. As I'm going through these sketches, I keep in mind the expressions of the human figures I drew before. And even if I wasn't deliberately trying to, their expressions would still be finding their way into the corners of the smiles and the eyes of the dragons. The human studies I did now inform the expressions on the faces of the dragons.

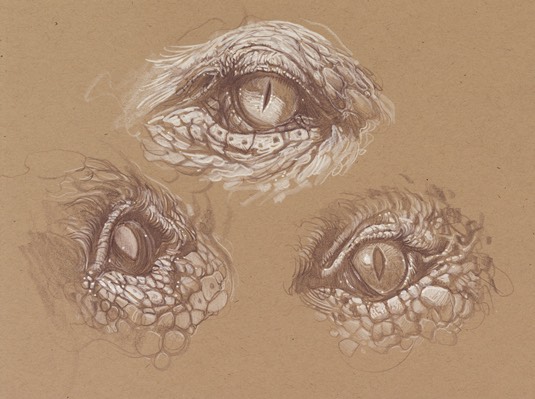

6. Drawing dragons' eyes.

The first place almost all biological creatures look when they identify another shape as a biological form is the eyes. They have been called the window to the soul. The same holds true for when we look at a character in a painting: we will generally always try to look at the eyes first, before we move on to the other aspects of the image. This is hard-wired into us as creatures.

So, it's important to capture the eyes correctly. Take some time and make studies of reptile eyes and human eyes. Find which ones are the most expressive. Which ones communicate what you’re after the best? Try combining them to achieve something new.

7. Work from memory.

By studying human facial expressions and working from memory, you will be able to merge the features and create a distinctive dragon with character.

As you execute your tight drawing, try to stick to what you have already memorized, as opposed to copying your reference. If you rely too much on copying, you'll slowly suck the humanity out of your dragon until it's simply a brute animal. Try to use your reference only to check your work or when you run into a problem.

8. Rough is good.

Don't worry about making these rough studies really tight. These are meant to be loose. Rough drawings like this are a great way to study expressions and to slowly build a mental library of expressions. As I do this, I ask myself what is it that makes this character look sinister, deceitful or devious?