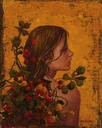

Books about, or illustrated by James C. Christensen:

“A Journey of the Imagination”

From Flying Pigs to Goblin Princesses

James C. Christensen's art travels a magical journey

By Carma Wadley

OREM

— It is a magic world, the one that artist James C. Christensen invites

you to enter. Fishes appear in unexpected locations. Boats carry

amazing cargoes to unknown destinations. Pigs fly; hedgehogs come in

heliotrope; goblin princesses have pet beetles.

In

this place, there are no limits to imagination and creativity. Yet

there is a lightness of being and an uplifting sense of purpose to it

all. You want to linger. You want to savor. You want to spirit a tiny

part of it away with you.

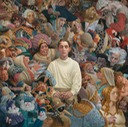

You

can see and do all these things and more in the latest compilation of

Christensen's work, a gorgeous coffee-table book book called "Men and

Angels: The Art of James C. Christensen" (Greenwich Workshop Press,

$85). The book, which was co-written by Kate Horowitz, features more

than 300 full-color paintings and a selection of whimsical sketches from

Christensen's private sketchbooks as well as anecdotes, thoughts and

descriptions of each piece.

Christensen

is one of the most recognizable and critically acclaimed living artists

in the United States today, says Scott Usher, president of Greenwich

Workshop Press. "We are very excited about the release of 'Men and

Angels.' His work communicates on a level that is as personal as it is

universal. He has the unique ability to give life to characters that

appear to be both human and divine."

The book is also a fun journey of discovery for Christensen. "I'm not fond of any of my pieces when I finish them. I'm just glad they are going away," he says. "It's like composer Merrill Jenson told me once, 'It's because we know where all the bent nails are.' But give me a year or two, and I come back and think, 'That's nice.' I've forgotten where the personal problem areas are."

When

people ask him which is his favorite painting, "I always say, 'The next

one.' I always look forward to starting a new one. Then I get so

involved I can't see it objectively. So, having a book with my work from

the past 10, 20 years, that's pretty exciting, pretty fun."

Plus,

he says, every artist dreams of "leaving the legacy behind. The book is

a nice artifact for my children and grandchildren." (He and his wife,

Carole, have five children: two daughters are now artists in their own

right; a third daughter teaches art; the two sons "are not involved in

art but are very creative people.")

When

Christensen takes time to reflect on his career, he's as surprised as

anyone, he says. "I didn't grow up in an artistic family. They liked

art, but I didn't even know what art supplies were. I got my first

supplies at Disneyland. They had an art shop in Tomorrowland that I

absolutely loved."

Growing

up in Southern California, "I drew as long as I've been alive." But it

took him a while to get into art. "I did one painting on my own in high

school, and it was horrible. I didn't discover oils until I was a

sophomore at BYU."

When

he gives lectures to students, "they always want to know what my

five-year plan was. The truth is, I didn't engineer any of this. I

didn't know who Greenwich Workshop was when they called and asked if

they could make prints of my work."

But

there's a bit more involved. "That sounds like opportunities just fell

into my lap, and some did. But I don't believe in blind luck. I think

you have to work hard, do your best, constantly try to improve and give

every project 100 percent. It follows that the harder you work, the

luckier you get." Still, he says, "you do have to be in the right place

and have the right things to say."

For

Christensen, the things he says have always bordered on the magical.

He's commonly called a fantasy artist, but he sees himself, rather, as

an artist who paints the fantastic. "That's actually a 17th-century

term, like the work of Hieronymus Bosch. I paint things that are not

real. But fantasy often ventures into the dark and scary stuff. I made a

decision long ago that I would not go to dark places. There's a lot of

negativity in the world. I try not to be part of it."

His

paintings are filled with symbolism. "There are many layers of meaning

in my work, and I love to play with themes and metaphors."

If

our lives are like rivers, he says, then boats are a good place for

things to happen. He also often uses fish. If you are fully dressed and a

fish is there, "it means you are somewhere else, a magical place. I

like to juxtapose things that you might not think would go together. I

get a kick out of putting in a lot of symbols and letting people find

out what they are."

He

wants his paintings to be "a point of departure. I don't demand that

the viewer finds out what I'm trying to say. If they have different

ideas, I say 'hooray.' Sometimes I like theirs better; sometimes I steal

those."

He

does want people to use their imaginations. "We all have that ability

to think creatively, but I don't think we use it enough."

He

also tries to "connect with common themes, the issues that people have

to deal with — the burdens of a responsible man." Ideas, he says, are

all around us, all a part of life. "I try to explore them in a unique

way. Most times it's a fun way, sometimes it's a touching way. But this

is stuff we all go through."

If

his paintings often have a spiritual side, that, too, is natural.

"Every authentic artist paints who he is. My religion, my spiritual

belief system permeate my life and my artwork."

There

are some artists who "feel that if you don't put great angst into your

paintings, you are not serving art. I don't buy that. My contribution is

to try to encourage people to be happy, to enjoy life, to be positive."

He

knows a man who hangs a Christensen painting in his bathroom. "He told

me that every time he gets out of the shower, he sees it and it makes

him laugh. I say good for him!"

Some

of Christensen's artwork hangs in his own Orem home. "Carole gets to

pick one painting a year to keep. That was her deal way back when I was

just starting to get successful. I've also saved a couple that

particularly inspire me, and things that don't sell have a way of

dribbling back."

Christensen

taught at Brigham Young University for 20 years but has since "quit my

day job." Over the course of his career, he has been accorded numerous

honors and awards. He was recently designated as a Utah Art Treasure,

one of Utah's Top 100 Artists by the Springville Museum of Art and

received the Governor's Award for Art from the Utah Arts Council.

He

has won all the professional art honors the World Science Fiction

Convention gives out and has received multiple Chesley Awards from the

Association of Science Fiction and Fantasy Artists.

"Men

and Angels" is the latest of several books he has produced, including

"A Journey of the Imagination: The Art of James Christensen," "Voyage of

the Basset," "Rhymes & Reasons," "Parables" (written by Robert

Millet), as well as a series of interactive journals — all filled with

art that Greenwich Workshop notes is "born from his keen observation of

humanity and his endless supply of imagination."

Christensen

just "feels fortunate I get to work at a thing I love to do. The more I

discover about the world, from biology to art history, the more

enthralled I am with the magic that is human existence."

All in the family: James C. Christensen joins forces with 2 daughters for art show

Like father, like daughters? Well, yes and no.

By Carma Wadley

Cassandra

Christensen Barney and Emily Christensen McPhie may have inherited some

of their father's (fantasy artist James C. Christensen) art genes, but

they also have developed different approaches and styles that give them

their own voices.

Which

makes it especially delightful, they say, on the rare times when the

get to "sing in harmony," as it were — when they get to have a joint

exhibition of their artwork.

One

of those occasions is an upcoming show at Art Access Gallery. The show

opens Sept. 18 and runs through Oct. 7. An opening reception will be

part of the September Gallery Stroll.

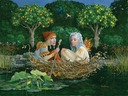

Another thing that makes this show so delightful, the artists say, is the theme: "Hortus Conclusus, or The Enclosed Garden."

They

were sitting around one day, talking about ideas, explains Christensen.

"I had done a 'Tree of Life' that was in an enclosed garden, and our

discussion took off from there. We found the Latin term, and we realized

there was a lot of symbolism, a lot of metaphors in the idea of an

enclosed garden."

The

traditional design of a walled garden, split into quarters separated by

paths, dates back to the earliest gardens of Persia, he says. "The

'hortus conclusus' of High Medieval Europe was more typically enclosed

by hedges or fencing, or the arcades of a cloister."

But

the idea of enclosure was to create a protected and nurtured space,

"where ideas and people, like plants and flowers, can flourish. The idea

of a controlled safe place can represent the family, the community or

even the space in one's own mind."

For

Barney, the idea "got me thinking about what I want in my garden. It is

an intimate space, where you can create your own paradise." In doing

research for the show, she says, "I was delighted to find that the word

paradise is, by definition, a walled garden. It is a place to learn and

grow and create beauty. It's a safe place where there is celebration.

But it also needs to be tended, because behind its walls is also a place

to be vulnerable. There can be hummingbirds, but there can also be

demons. This has been one of my favorite themes to work on."

As

a mother of young children, McPhie's thoughts "immediately jumped to my

kids." Her marionette-like images for the show "are a comment on

parenthood, on how many decisions I make for them each day. And how do I

know when it's time to cut the strings? When is it time for them to go

outside the wall? There are so many emotions that go with those

decisions."

And

that, Christensen says, is really the fun part of working with his

daughters — "the ideas bouncing back and forth, the what-iffing, the

planning. I love these collaborations."

But

it's not like they ever exactly planned on being a family of artists.

"When we were growing up, Dad didn't push us to do art at all," Barney

says. "I didn't ever think that I would be an artist." In fact, she was

going to major in physical therapy — until she got to the first day of

classes. "I realized that I didn't want any of those classes; I wanted

to take art classes instead. I finally told my dad about halfway through

the semester."

That

was when she was attending what was then Ricks College (now BYU-Idaho).

"We took a physical therapist up and brought an artist daughter home,"

Christensen jokes.

But

he thinks that "part of the reason why Cassie and Emily are artists is

because they were not forced into it. I thought that I was the anomaly,

and they would grow up to be real people. But I always had the art

supplies around. If they wanted to color, they had 120 colored pencils

to choose from and a hundred colored markers."

He

also knew, however, that they would have to develop their own passion

for art. "My philosophy is that art is passion-motivated. Without

passion, it's just too hard. Passion leads to the desire to spend the

hours that are necessary. Passion leads to the work ethic. Passion means

you are willing to go under 'studio arrest' for periods of time."

And

that, says Barney, "is the thing that rubbed off on us. Dad had that

passion. We had his example of loving what he was doing. And he worked

hard at it. He would teach all day, and then come home and have supper

and do the family stuff, and then he would go to his studio and paint."

Christensen

is equally proud of his two non-artist sons. His middle daughter,

Sarianne, "works with me in the studio, hand-tinting art, and is head of

the art program at Pleasant Grove High School. She also does ceramics.

But she loves working with the kids."

But

it also has been satisfying to see his oldest and youngest daughter —

they are separated by 10 years — come into their own as artists.

For

the first few years, when they did something together, "it was, here's

James Christensen and, oh, by the way, he has daughters," he says. "But

the last year or two, it's getting to where they attract more attention

that I do. Cassie and I did a signing in Boise, and she had huge lines

at her table. The guy in charge asked me if I'd like him to slip people a

dollar to come see me. They don't need me anymore," he jokes.

Part of it, he says, "is because they blog. They blog worldwide" — Barney at churningsandburnings.blogspot.com; McPhie at tendernessandtoil.blogspot.com — "and now it's like they have best friends all over the world. They

have a tremendous following. They put their lives out there. They talk

about canning peaches. It's a way to connect with people that also helps

people connect with their art."

Barney

and her father get to interact frequently because they practically live

across the street from each other. Christensen will come and look at

one of Barney's paintings for the show that she is struggling with. "You

don't need to change it," he will tell her, "you just need to change

the way you look at it. You're going with the medieval fear-of-void

concept. Just pick a light source and add some shadows." Then, he adds,

"Tomorrow, she'll come over and fix my painting."

For

McPhie, who lives in Arizona, the constant interaction is a bit harder.

"But I get to come spend a month each summer," she said in a telephone

chat. "I get to paint in my dad's studio. I get to go shopping with them

for art supplies. That's the most fun thing — to stand in front of a

wall of colors and say, 'Have you tried this one?' or 'You've got to see

what this one does.' Of course, it was more fun when Dad paid for them

all."

It

was only when she got married and began to deal with in-laws, McPhie

jokes, "that I realized how odd my family was. Do you know there are

people who go to Europe and only go to one museum? I always thought

museums were the only things in Europe."

But

growing up, "I had a lot of influence, a lot of appreciation. I had

classmates who had parents who didn't see the value of art. I never had

to worry about that. And I kind of fell into it naturally. I also had

Cassie to look to; I learned a lot from her experience as an artist and

as a mother."

And

while there never has been any rivalry, says Barney, with a grin, "We

have learned that if you have a good idea, it's better not to tell

anyone about it, or they'll grab it. We do overlap a lot. Sometimes, we

simultaneously paint a unicorn tapestry. It's so bizarre."

But

even then, they do it in their own way. "Cassie paints something, and I

come over and it means something different to me," says Christensen.

And that, he says, is the pure joy and extreme value of art. "It can

have a lot of meanings. It's open-ended. It has the potential for people

to find their own meanings in it."

And that's exactly, he says, what the song of "Hortus Conclusus, or The Enclosed Garden" is all about.

Notes from a Lecture by James C. Christensen, March 5, 2010

On Friday, March 5, 2010, I attended a lecture by James C. Christensen at the Bridge Academy of Art in Provo, Utah. A truly fascinating experience. Below I’ve included some notes I took from his lecture:

• Influences:

Northern Renaissance

quirky perspective

attention to detail

Bosch

Brueghel

Durer

19th Century Romantics / Pre-Raphaelites

Leighton

Waterhouse

Dore

• Paints “slower than the drift of continents.”

• ”The harder you work, the luckier you’ll get.”

• Likes the work of Andrej Dugin and Olga Dugina.

• According to BYU professor Martha Peacock, “He (JCC) was born in the wrong century.”

• William Whitaker, a fellow professor at BYU, taught him how to paint in oils.

• Has a hard time working for money -- has to love what he’s doing; needs to be excited about it.

• Put in the time. Get good. 10,000 hours (Malcolm Gladwell’s “Outliers”) of practicing your craft is what it will take to get good.

• Worked on the murals for the Nauvoo Temple.

• Uses small sable hair brushes for his work in oil.

• Contributed to the book, “Star Wars: Visions.” He painted a Cantina scene from Mos Eisley on Tattoine.

• Making money on PRINTS (Greenwich Workshop) and the originals allows him to justify to amount of time that he puts into a painting.

• Has 57 volumes of sketchbooks, works almost exclusively in ink, and relies on them for ideas, working out compostions, observational sketching, etc.